Section Two

Module 8: Sociocultural Dialects

-

Is my knowledge of dialects a stereotype?

-

After working with the material in this module, readers will be able to

still need these for this module!

Module 7 emphasized geographic variations in American English. As you know from your own life, however, our dialects (or Englishes) also reflect our racial, ethnic, national, religious, generational, and other sociocultural backgrounds, in many ways. More importantly, our views of other people’s dialects often turn out to be intertwined with our views about their race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, age, and other sociocultural variables, sometimes in simple or fun ways but often in problematically stereotyped ways. The material here in Module 8 explores some of these complex ideas.

Not Noticing Speech Differences That Do Exist

The previous two modules addressed the wide variety of languages and dialects that are used across the entire U.S. and its territories. Try thinking for a minute about a very narrow, self-centered version of this question, similar to the question about languages that we asked at the beginning of Module 6: How many different dialects or accents of English have you heard in the last month or so?

If your answer was that you have heard primarily only one or two dialects, try approaching the question by thinking about the speech of every individual person you have talked with or overheard. They were probably each speaking in slightly different ways, many of which you may have not noticed at the time but can make yourself aware of if you think about it.

If your neighborhood, community, or work setting does include many distinctly different accents or dialects, leading you to have guessed that you have heard perhaps 5 or 10 dialects, or more, try the same exercise: Think about the speech of each individual you have heard. Did the people you had categorized as speaking the same dialect really speak exactly the same way, or were there actually even more differences than you had originally counted?

In my own case, my first answer at one level might include counting my husband, our children, and myself as demonstrating one speech pattern that is similar to the speech pattern used by many of our friends and colleagues. At another level, though, when I stop to notice, we do not speak the same way at all! I grew up in northern California and then moved to Georgia, my husband grew up in southern Louisiana and worked in New York, and our children grew up in Georgia several decades later. We are a household with three subtly but distinctly different dialects, when I take a moment to think about it – and that’s before I leave the house.

Why do we not tend to think about it? We notice some accents or dialects, of course, but as we go about our daily routines we tend not to focus on the fact that almost everyone around us is speaking slightly differently from everyone else. Linguists describe this phenomenon by saying that many of the differences among other people’s speech patterns are “not salient” for us, meaning that we do not notice those differences (see Boswijk & Coler, 2020, for a discussion of everything “salience” can mean). But how and why can we manage to ignore so many differences in each other’s speech?

Part of the answer comes from your first speech science course: Speech perception and comprehension actually depend on and require listeners’ necessary ability to ignore most acoustic differences, within and across speakers. The miracle of speech perception is not that every speaker produces identical acoustic signals; the miracle of speech perception is that every speaker produces unique and complex acoustic signals and that listeners somehow know which few of the many across-speaker and within-speaker acoustic differences are meaningful. At other cognitive and social levels, we also ignore differences in each other’s speech patterns because we are focusing on the content of the message, have gotten used to the differences, expect the differences, perceive the differences as small when we do notice them, or, generally and most importantly, because in some way we do not believe the differences matter. The differences are there, acoustically, but socially and interpersonally we do not notice because we do not find them significant and because we are focusing on other things.

It is important for us as speech-language pathologists to be aware not only of language use patterns across the entire U.S. but also of the wide variety of accents, dialects, and idiolects (individual speech patterns) of English that we ourselves are surrounded by. It is even more important for us to be aware of our tendency not to notice those variations. When we do notice a difference, and we then find ourselves about to suggest that a dialect or an accent is causing a problem, or that a speaker might need or want to change any characteristic of their dialect or accent, we would do well to remember that a mere difference in speech or language production is probably not the issue. Again, we are all surrounded constantly by a wide variety of speech and language patterns, including many different accents and dialects, that we do not notice, that are not salient for us, and that do not interfere in any way with communication. The point here is that differences in speech and language patterns, as linguistic differences, are probably not the problem.

Your Turn

Try listening actively to the speech of people around you for the next day or two at work, at school, and in public places, using an initial assumption that everyone speaks differently. Can you become aware of differences in people’s accents or dialects that you had usually tended not to notice?

Phoneticians and phonologists have devoted considerable theoretical and experimental energy to questions about whether speech is overlapping physical continua or divisible units or both (see Ladd, 2011, and then Kohler, 2013). How can models such as the tendencies of groups to gather around one portion of a longer dimension, or models that help us visualize individual characteristics as existing along continua that people tend to judge as better or worse (i.e., Hofstede’s and Morgan’s models, from Module 2), help us think about why we do not notice the substantial speech-production variations that exist around us all the time?

Judging Speech Differences That Do Not Exist

The overall point of the previous section was that we often do not notice many of the linguistic differences that surround us daily. That was an awareness and acceptance exercise, similar to our discussions of languages and multilingualism in Module 6. We are routinely surrounded by multiple dialects and accents of English, a fact that not only does not interfere with communication or cause any other problems but that, often, we do not notice at all.

Equally problematic, as we think about sociocultural dialects, is that the opposite also turns out to be true: Listeners hear and judge dialectal differences that are not there.

How can such a thing be possible? You might already be familiar with this phenomenon, but let’s start with a research paradigm called matched guise experiments and try to explain.

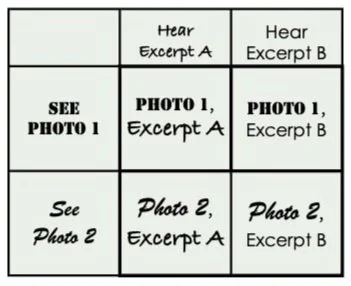

Imagine a research study that requires you listen to brief recorded excerpts from a lecture. The recordings are audio-only, but you can see a photo of the speaker as you are listening. At the end of each recording, you are asked to rate the speaker on one or more scales, or you are given a comprehension test about the material, or both.

Now imagine the many ways that researchers could manipulate this situation. The audio recordings might be sped up or slowed down or altered in many other ways. The photographs could be altered, or the photographs and the recordings could be decoupled, such that you would see one person’s photograph while you were listening to a recording of another person’s speech. The content of the lecture could be altered in minor or more substantial ways. The researchers could tell you they had made these manipulations, not tell you, or even lead you to believe that they had made other manipulations, depending on what they were studying and why.

Many socio-linguists and other researchers have used versions of this experimental protocol to study the influence of speech-related stereotypes on listeners’ judgments about, and comprehension of, recorded speech samples. In one classic and representative study (Kang & Rubin, 2009), the recordings were not altered, but the photographs were decoupled from the recordings, and the entire situation was manipulated to make listeners believe they were hearing two different speakers even though there was only one speaker.

The single speaker was a White man from Michigan who spoke what Kang and Rubin described as “standard American English,” but his picture was never used.

Instead, as they were listening to recordings of this one man’s speech, listeners saw either a photo of another White man, described to them as a “Euro-American” instructor, or a photo of an “East-Asian” man, described to them as a “Chinese” instructor. They were led to believe, and allowed to believe, the perfectly reasonable assumption that the person they were seeing was the speaker they were hearing. The men in the photographs were similarly dressed, were of similar size, had similar hair, were photographed in the same setting and pose, and had been rated previously as having similar “attractiveness” (which is important because perceived attractiveness influences judges’ ratings of speakers).

Two 4-minute excerpts were taken from the one original audio recording, so the content of each excerpt was similar but not identical. Pairings of the two audio samples with the two photos, and the order of presentation, were both counterbalanced across participants. All participants also heard another (distractor) speaker, with a third photo, in between the two experimental samples, masking the fact that the same speaker was used for the two experimental excerpts. At the end of each excerpt, the listeners rated the speaker’s accent, rated the speaker’s quality as a teacher, and completed a listening comprehension test about the material.

Did you follow all that? Listeners heard two brief excerpts taken from within the same single audio recording of one “unaccented” speaker of “standard” American English, but they believed they were listening to the speech of two different speakers, one of whom they perceived as Euro-American and one of whom they perceived as Chinese. After each excerpt, they rated the speaker and were tested on how well they had understood the material.

What do you think happened?

If you are familiar already with this matched guise technique, if you have learned before that negative “ideologies” about groups of people actually affect linguistic perception (see, among many other examples, Weissler’s 2022 summary), or if you are personally familiar with being misjudged by other people on the basis of their uninformed prejudices about you, you have probably guessed at least part of what happened, but the extent of Kang and Rubin’s (2009) findings was genuinely remarkable.

Both excerpts, produced by a single original White speaker from Michigan, received stronger accentedness ratings and lower instructional-quality ratings when listeners believed the speech came from a Chinese speaker (as measured by the listeners’ ratings about their perception of the speaker’s background), as compared with when listeners believed the speaker was White. Even the listeners’ comprehension test scores were lower for the segment of speech they believed to be from the Chinese speaker than for the segment of speech they believed to be from the White speaker.

The listeners’ judgments about, and comprehension of, the speech they heard were clearly influenced, in other words, by factors that had nothing to do with the speech; in fact, approximately 10-20% of the variance in listeners’ judgments and comprehension could be related to their assumptions about the speaker’s background, not to the actual speech at all.

Sit with these findings for a minute. What are these data trying to tell us about sociocultural dialects?

Understanding the Results of Matched Guise Experiments

Step back for a moment and think about how discussions about accents and dialects are often framed. The focus is often on linguistic features; that is, we tend to explain an accent or a dialect by describing or comparing articulatory details, phonological patterns, missing or extra morphemes, syntactic structures, and semantic items. Such explanations assume that an accent or a dialect is perceived when the speaker’s linguistic patterns become salient for the listener because the speaker’s linguistic patterns differ from the listener’s, differ from the listener’s expectations, or differ from how most speakers in the immediate area tend to speak. This “noticing” on the part of the listener might be affectively neutral, if it is perceived purely as a linguistic difference, or affectively positive, if we perceive that a speaker is using an accent or dialect that we like or that carries some positive connotation for us.

Negative judgments about dialects are assumed to occur, in this mindset, when listeners perceive differences in the linguistic details of the speaker’s speech patterns that, to the listener, are problematic in some way. You might have heard some versions of African American English described this way, or you might have been asked to memorize at some point that Black English “omits” what an author or an instructor decscribed as a “necessary” possessive morpheme (i.e., using a structure such as “my friend cat” to refer to the animal that other speakers believe should be identified as “my friend’s cat” might be described as missing or dropping the apostrophe-s marker of ownership). Depending on how much you know about specific accents and dialects, you may be able to think of many other examples.

But what do Kang and Rubin’s (2009) data show us? The listeners’ negative judgments about the speakers’ accents, and the listeners’ judgments about the speakers’ poor teaching ability, could not have been based on judgments about linguistic differences, because there were no linguistic differences. It was not “speakers” at all. It was one speaker. The recordings that the listeners judged to be more accented were the same recordings, or had been produced by the same speaker of “standard American English” during the same lecture, as the recordings that the listeners judged to be less accented.

The phenomenon demonstrated by the matched guise research is known as “reverse linguistic stereotyping.” The “reverse” part of this label refers to the fact that, rather than hearing differences in speech and making stereotyped judgments about the speaker (which does occur, often, and is referred to as linguistic stereotyping), something else was happening: The listeners’ perceptions of the speech they were hearing were affected by their preexisting stereotypes about the group of people they believed the speaker to belong to. When listeners (incorrectly) believed the speaker to be of a particular racial or national background, they heard an accent that was not there, judged the same speaker to be a poorer instructor, and even understood less of the material.

Depending on the experiences you have had in your life with your speech, these results might seem farfetched, might describe your all-day-every-day, or might fall somewhere in between. If you are less familiar with the phenomenon, you might want to find and read any of the many other experiments that have used the matched guise protocol and found essentially the same results (see Drager, 2010; Giles & Billings, 2004; Rubin, 2012; Ryan & Giles, 1982; or see Weissler’s 2022 summary, which also addresses the related neurophysiological data that support and extend the same conclusions). Some studies focus more closely on speech variables: Hay et al. (2006), for example, showed that listeners heard specific phonemes that the speaker had not actually produced, based on their beliefs about the speaker’s dialect. Lee and Bailey (2022) recently replicated Rubin’s work in Japan; in this case, Japanese participants reported hearing a stronger “non-native accent” in the same recording of one native Japanese speaker when they believed him to be Caucasian than when they believed he was Japanese. Rubin and colleagues also expanded their work to the important arena of patients in the U.S. understanding or not understanding healthcare workers from other countries (Rubin, 2012). The detailed results from these studies differ in some ways, but overall, a large body of matched-guise linguistics experiments has demonstrated, clearly and repeatedly, that listeners judge the speech they think they are hearing, and judge many other abilities of the person they think they are hearing, through the filter of their stereotyped beliefs about people from “that” background, even when the speech characteristics they think they are hearing simply are not present in the speech signal at all.

Your Turn

I do not mean to skip over the “regular” kind of linguistic stereotyping, the kind that results when a listener hears a linguistic pattern and leaps to unwarranted personal or social assumptions about the speaker. It happens, and it’s a problem. Explain why “reverse linguistic stereotyping” can be seen as even more of a problem and also as a potential underlying contributor to linguistic stereotyping.

Are you aware of ever having made any judgment about another person based on some initial oversimplified assumptions that turned out to be completely wrong? Your judgments were probably not conscious or explicit, but as you look back you might recognize that your thought process noticed that the new person had some trait, characteristic, or ability and then assumed that they must have some other trait, characteristic, or ability which they turned out not to have. (If you are tall, you might get very tired of people assuming you play a particular sport or telling you that you “should.”) Why do you think people tend to make such judgments about other people? When do these quick judgments help us, and when are they problematic? How do they influence our relationships with clients and families?

Do you remember being aware, in your undergraduate courses, that some students seemed to have more or less trouble understanding some instructors? As you look back, do you think any variables other than the instructor’s speech could have been involved, when some of your fellow students reported that they did not understand some instructors’ speech? (Research about student evaluations shows very clearly the same issues that matched-guise linguistics experiments show; instructors from certain familial backgrounds are routinely rated as poorer teachers, even when every objective measure about their speech, their courses, and their teaching is equivalent to those of instructors who are rated more positively by students.)

Raciolinguistics: Dialects, Race, and People

The first parts of this module established two important points:

In many daily situations, we do not notice the many accents and dialectal differences that surround us almost constantly. Differences in accents and dialects do not necessarily cause communication breakdowns; in fact, we usually do not notice other people’s accents or dialects at all.

In experimental situations, listeners have been repeatedly demonstrated to perceive accents or dialectal differences that do not exist in the speech signal, and to make negative judgments about both the speech and the speaker on the basis of their incorrect perceptions, in ways that have been experimentally shown to be connected to the listener’s beliefs about the race and/or national background of the speaker.

We need to consider one final and common situation: Listeners often do notice the real accent or dialect of a real person in a real-life situation. We can usually both see and hear the speaker, and we are almost always correct in assuming that the speech we are hearing is being produced by the speaker we are seeing. We also often have at least some correct information about what we might describe as the speaker’s racial, ethnic, cultural, national, or familial background. What happens in these situations? When we notice that someone speaks differently from the way we speak, what are we noticing, what are we judging, and why?

Yes, We Are Talking About Race.

One of the things we notice, in many situations, is what we believe to be the speaker’s race, ethnicity, national background, or family background, so let’s go ahead and talk specifically about these variables and about their relationships to language. To do so, we need to start by accepting and normalizing, first of all, that the constructs many people tend to refer to as race, ethnicity, and national or familial background can reasonably enter our thinking about speech and language.

(This discussion avoids the question of whether race “exists,” because most people think they know that it does and because some of the constructs that people tend to be refering to when they use this word affect our practice. If you are not familiar with the question or with its complexities, you might want to explore Rogow, 2003, and the other resources available at https://www.racepowerofanillusion.org/ . )

It is not wrong, racist, trendy, progressive, political, politicized, “woke,” or otherwise problematic to be aware that people live in different countries, speak different languages, speak different dialects, have cultural and personal backgrounds that often relate in part to where they and previous generations of their families have lived, and can look different from each other in some ways. Similarly, it is not wrong to assume that the members of a reasonably defined group of people may have some characteristics in common. In fact, as we addressed in Module 2, the members of any group must have something in common, if they are to function as a group, and identifiable groups of people do tend to cluster along subsections of multiple descriptive dimensions – including which dialects of which languages they tend to use to communicate (Hofstede, 2011). Languages and countries and people’s backgrounds are imperfectly related, of course, but they are undeniably related; indeed, we defined languages in Modules 6 and 7 in part by referring to nations or political divisions.

Bringing race, ethnicity, and family or national background into a conversation about dialects and languages, in other words, is necessary, not problematic in itself.

The problems that tend to connect dialect and race begin to arise, especially in a country as multiethnic, multiracial, multilingual, and multidialectal as the U.S., when listeners’ beliefs about other people, and their resulting judgments, decisions, and actions, go beyond a simple, accurate, descriptive awareness of true group tendencies. It is one thing to believe, as one example, that many people in Japan have dark hair and speak Japanese. It is another thing entirely to believe that people in the U.S. who look as if they or previous members of their family might have come from Japan are bad instructors.

As extreme as that example might sound, real-life examples of such incorrect negative judgments about complete people are widespread. You might be able to think of examples related to recent events in your own life, the lives of your family and friends, or in your town. You might also be able to remember examples that made national headlines, or you might be thinking of patterns of human behavior that you know about from around the world or throughout history.

We can also gather many examples from many types of real-world and observational research. In legal research in the U.S., for instance, jurors have repeatedly been demonstrated to perceive witnesses, defendants, and attorneys who speak African American English more negatively (i.e., as less professional, less educated, less trustworthy, and more likely be guilty), as compared with how they perceive witnesses who use a Western or Northern American English dialect (see Kurinec & Weaver, 2019). In a completely different realm, Chicano English, Russian-influenced English, and Italian-influenced English are routinely used intentionally for television and movie characters because these accents and dialects are reliably interpreted by audiences as signaling gang membership or the character’s tendency toward violence (Lawless, 2014). In one example from management research that I find particularly striking, Post et al. (2009) studied analyses of “managerial potential” made by higher-level administrators about engineers from India who were working in the U.S. After examining multiple variables from the speakers and from the administrators, Post et al. concluded, among other findings, that “the absence of insecurity in Indians’ self-reported English fluency [was] detrimental to the evaluation of their managerial potential” (Post et al., 2009, p. 241).

Can you work out what that last sentence means? Engineers from India, working in the U.S. and with any “managerial potential” at all, would have come primarily from relatively privileged socio-economic groups. They would have been natively bilingual (in Hindi and English, for example), or they would have learned English in school starting at a relatively young age and used English extensively in their schooling and their profession. They probably reported no insecurity about their ability to use English for the same reason you might report exactly the same thing: You are, correctly, secure about your ability to use English.

The managers evaluating these engineers, however, assumed that the engineers’ English would be poorer because they were from India or judged the engineers’ Indian English to be in some way worse than their own (the managers’) American English. As a relatively predictable next step, the managers then interpreted the engineers’ self-report of feeling secure about their ability to use English as if it reflected a problematic lack of self-awareness, even though the managers had not measured the engineers’ self-awareness and had no information about the engineers’ self-awareness. The managers had leapt all the way from their stereotype that people from India do not speak English well, to assuming that the engineers who reported feeling secure in their ability to use English must lack the self-awareness that a good manager needs, to rating the engineers as less prepared or less qualified than other people for managerial positions because of their lack of self-awareness.

Post et al.’s (2009) study, and the many other examples we have mentioned, all demonstrate some core aspects of a field that has recently been named raciolinguistics (see Alim et al., 2016; Rosa & Flores, 2020). As Rubin and colleagues had previously noted, raciolinguistic assumptions exist and can be primed by either piece of information; that is, knowing (or believing we know) either the speaker’s race or the speaker’s dialect, or both, tends to activate listeners’ assumptions about both race and dialect. As a result, in real-life situations, listeners’ perceptions, beliefs, and ensuing decisions about speech and also about speakers are often influenced by their initial judgments about the speaker, including an initial judgment that the speaker looks to be a member of what the listener believes to be a particular racial, ethnic, social, or other group. Some of the prejudices demonstrated in these situations have also been described as implicit biases, if the judge is unaware of holding the belief that their decisions or actions demonstrate (see Blair et al., 2011, for a discussion about implicit and explicit biases in healthcare), and they are related to the constructs also described as microaggressions (see Williams, 2020, and Williams et al., 2021). Rosa (2019) described the many problematic raciolinguistic assumptions that people hold by noting that sometimes people act as if a person can “look like a language” or “sound like a race” – something that is especially problematic when the judge’s views of the dialect, language, or race in question are negative and wrong.

Considering Some Implications

How are you doing with this discussion? Are you cheering, dozing, or feeling annoyed again about the social-justicey feel of it all?

Once again, let’s gently remind ourselves and each other that we are each on our own journeys; we all encounter information through the lenses of our previous experiences and current beliefs.

Wherever you might be in your journey, though, do you see the important implications here for your practice or for our entire profession?

Race has been intertwined with language throughout human history in many ways, some of which many of us now judge, from our current perspectives, to have been problematic. Sometimes race, ethnicity, or national or familial background ended up related to language because of military or other takeovers of lands and peoples and the resulting imposition of languages (as Kahra’s three-circle model for World Englishes recognized, from our Module 7; see also Von Esch et al., 2020, for one recent review focused on language teaching around the world). Sometimes, race, ethnicity, and familial background ended up related to language because of one country’s social history, including immigration patterns or a history of certain groups being enslaved by other groups. Because of the sensitive nature of these topics, and because they can be interpreted in many ways, daring to mention race at all is often seen as problematic, for a wide range of reasons — as has emerged in many political discussions in the U.S. during the mid 2020s, and as Von Esch et al. (2020) addressed for language teaching (see also Lilienfeld’s 2017 objections to the construct of microaggressions and, especially, Williams’ 2020 response).

To be effective in client-centered, culturally and individually appropriate speech-language pathology, however, we must be willing to discuss race, because we must recognize who we are, who our clients are, and how the people in our communities have interacted over time. The basics of clinical service delivery in speech-language pathology start with interacting respectfully and compassionately with real people, developing a complete understanding of a real person’s speech and language, and then making decisions with them about which next steps make sense for them in their contexts. We simply cannot achieve those goals if we are at the same time somehow trying to completely ignore large parts of people’s contexts.

We also must think about race in speech-language pathology because the matched guise research, other research from raciolinguistics, and substantial other information also shows us that when we think we are noticing a speaker’s dialect, and when we believe we are making clinical or professional decisions about a speaker’s dialect, something much more complex might be happening. Remember: Kang and Rubin’s listeners decided that the speaker they were hearing was hard to understand, Hay et al.’s (2006) listeners decided they heard specific phonemes that the speaker objectively had not produced, and the administrators in Post et al.’s (2009) study decided that the engineers from India they worked with had limited self-awareness in ways that would limit their ability to serve as managers. What if our own clinical and professional decisions are being similarly influenced, at some level, by our underlying stereotypes or biases about our clients’ and colleagues’ dialects or about their racial, ethnic, national, regional, or religious backgrounds?

As Lippi-Green (2012, p. 335) concluded, biases, stereotypes, and discrimination based on dialect or language are not limited to decisions about specific speech or language features but are related, instead, to the negative “social circumstances and identities” that listeners incorrectly associate with that dialect or language. Our judgments about dialects, in other words, often are not judgments about speech or language patterns at all; they are judgments that stem from our underlying, and often unlearned and unrecognized, beliefs, stereotypes, or prejudices about groups of people.

The implications for us as speech-language pathologists are complicated but important: As we think about accents and dialects, we probably need to focus our energies less on phonological patterns or specific morphemes and more on understanding and reducing the continuing influence of race-based and other social stereotypes in our society, in our profession (see Holt, 2022; Yu, Nair, et al., 2022), and possibly even in our own decision-making. The information provided by raciolinguistic research serves as important fundamental information and can help each of us, as the unique individuals that we are, to think about how we might make our best contributions to our profession and to our society.

Your Turn

How are you doing, as we talk about race and racism? What about your journey so far in your life leads to how you are doing now — and how will all those pieces influence your ability to provide client-centered, culturally and individually appropriate speech-language pathology services?

Try using our general theme of dimensions and continua to think about people’s responses to discussions about racism. One end of the continuum might be complete rejection of the entire notion: refusing to acknowledge that racism exists, not accepting any examples, focusing on counter-examples, and seeking other explanations for whatever has happened. [As I suggested above, I would describe Lilienfeld’s (2017) critique of microaggressions as an example of this tendency; see it and Williams’ (2020) comprehensive response.] The other end of this continuum might be a determination to insist that everything is the result of racism, or a determination to seek race-based explanations when race genuinely was not the operative variable or honestly had nothing to do with what was happening. If you can, depending on how race-based discrimination has affected your own life, try discussing some of the many points along this continuum, for dialects and accents, with as much kindness and respect as you can. Why might people seek, leap to, accept, resist, explain away, or completely reject any notions of racism as they think about dialects and accents? How does such a continuum affect your work, as you seek to provide speech and language care to “all populations” (ASHA, 2017)? (If you have never experienced other people’s negative judgments or discrimination about your own speech or your own background, be aware that this will be an abstract or academic conversation for you but a very personal one for your colleagues who have been so affected. Accept their experiences.)

Imagine that Peter and Mary are speaking to each other, each using their own primary dialect of the same language. During their conversation, Mary finds Peter hard to understand, but Peter has no trouble understanding Mary. The problem cannot be the simple linguistic distance between their dialects, because the distance from Mary’s dialect to Peter’s is the same as the distance from Peter’s dialect to Mary’s. Drawing on the evidence discussed in this module about the influence of sociocultural stereotypes on perceived intelligibility, can you discuss what might be happening? What else might be happening? How could Mary and Peter improve their situation?

What range of possible creative, collaborative, or combinatory solutions exists, when any two genuinely well-meaning people using any two different dialects of American English genuinely want to understand each other?

I have referred to Yu, Nair et al.’s (2022) article more than once now, but I have done so without actually describing for you their main premise, logical conclusion, and recommendation: that our work as speech-language pathologists should focus much more on educating listeners about the acceptability of all accents and dialects (emphasizing the domains of professional practice) and focus much less on educating speakers about how to speak differently (de-emphasizing the domains of clinical service delivery, even for “elective” services). Find their article, read it carefully, and discuss it with friends or colleagues.

Highlight Questions for Module 8

Imagine any two speakers. Explain the differences in their spoken expressive language at several levels (e.g., as an acoustic signal, based on their age, because of their occupations, because of where they live, etc.). Which of the differences in their speech, voice, and language would be salient to them, and which would not? Why does it matter to our practice of client-centered, culturally and individually appropriate speech-language pathology for us to be aware of the wide variety of speech, voice, and language differences that we do not notice?

Explain the basic strategy used in matched-guise linguistics research (e.g., Kang & Rubin, 2012). Explain the overall results of the body of work that has used this strategy.

What is “linguistic stereotyping”? What is “reverse linguistic stereotyping”?

Why does it matter to our practice of client-centered, culturally and individually appropriate speech-language pathology for us to be aware that listeners often judge speech, and judge many other abilities of speakers, through the filter of their stereotyped beliefs about people from “that” background?

What is in the regional or national news at the moment, as you read this module, about accents, dialects, raciolinguistics, or racism generally? How do your experiences so far in your life lead you to respond to such sociological or political issues? How does that response, in turn, influence your ability to provide high-quality services to “all populations” (ASHA, 2017)?

This website does not include summary charts along the lines of “The Phonological and Morphological Features of Dialect X and Accent Y,” primarily because I believe most such resources to be affected by the same kinds of problematic filters that the matched-guise research reveals. For sociocultural dialects in particular, even some of the most objective and useful information still tends to use phrases such as “linguistically impoverished,” “a plural may be unmarked,” or “lack of melodic variation” (from Charity’s 2008 descriptions of African American English). Hendricks and Adolf (2020), similarly, described children who spoke “nonmainstream American English dialects” by saying that they “overtly marked past tense and third-person singular less often” as compared to their peers who spoke “mainstream American English.” ASHA’s materials for clinicians currently link to a resource that uses the same sorts of words we use for phonological disorders to describe the “characteristics” of the African American Vernacular Englishes (e.g., deletion of, substitution of). Do you see the subtle but critical filters in place here? Hendricks and Adolf (2020) meant that some children did not use the same “-ed” verb ending that other children used, but they phrased this tendency by saying that the children “marked past tense…less often” instead of saying that the children “marked past tense semantically” (which is what happens: the children obviously understood the differences among past, present, and future timeframes, but instead of “he walked to the store yesterday,” some dialects use “he walk to the store yesterday,” allowing the “yesterday” to mark the past tense — that is, the past tense is marked semantically). Plurals is another of my favorite examples: I would describe the dogs in the park as “four dogs.” If I have already told you that there are four of them, though, then do you need the “s” that I add to the end of “dogs” to understand that there is more than one dog? You don’t, but I have never been told that my dialect overmarks plurality, much less ever had to prove to anyone that my use of “four dogs” is not a disorder (and then been sent away, having been labeled “different in such a problematic way that it took a professional to figure it out”; see Module 14). All that having been said, and even though this module emphasized that many decisions about speakers and about their speech are made on the basis of non-linguistic variables, it will also be important for you to be familiar with the phonological, morphological, syntactic, and semantic features of the dialects that are common in your geograhic area. Use ASHA’s website or other trustworthy resources to find some intitial information; then be sure to critique the filters that are obvious in that information, and be sure you can explain it in both directions (as compared with Dialect X, Dialect Y does this; as compared with Dialect Y, Dialect X does this) and in truly neutral terms (in Dialect X, the underlying construct of Z is conveyed like this).

Module 8: Copyright 2025 by Compass Communications LLC. Reviewed March 2025.