Section Five

Module 19: Cross-Cultural and Cross-Identity Clinical Service Delivery

-

How do I provide the best possible cross-cultural communication care with this individual client?

-

After working with the material in this module, readers will be able to

understand ASHA’s required actions for culturally responsive clinical service delivery

explain the complexities of an interpersonal and cross-cultural bridge-building metaphor for individual communication care

access and evaluate necesary information about cultures and identities

select from among a dozen specifically cross-cultural techniques to provide high-quality individualized communication care to all clients

High-quality clinical service delivery requires a strong cross-cultural therapeutic bridge between you and your client. This module discusses ASHA’s cultural responsiveness requirements, the realities and complexities of interpersonal bridge-building, resources for accessing the detailed information you need about a client’s cultures and identities, and 12 specific techniques for successful cross-cultural clinical interactions with individuals.

Be sure you understand the distinctions between “multi-” situations and “cross-” situations, and the constructs of universal needs and specific needs, from Module 15, before you try to read this module.

Our last several modules addressed multi-cultural approaches and multi-cultural groups. Let’s shift our thinking now to one-on-one clinical service delivery or communication care: one clinician, one client, and one cross-cultural therapeutic bridge.

Here’s a funny question to get us started. Are you the exact same person as any of your clients?

(No. Of course not.)

Here’s an extension of the same question: Imagine any client who is not you. Do you structure that client’s therapy as if the client were you, or do you structure that client’s therapy in a way that you intend to be useful for them?

(The latter. I structure my clients’ therapy programs in ways that I intend to be useful for them, not as if I were the client.)

Okay, and, here’s a pile of “what if” variations.

What if the client plays with toy cars and you don’t? What if the client has two dads and you don’t? What if the client eats with a fork and you eat with chopsticks? What if the client wraps her hair with a scarf or a veil and you don’t? What if the client likes Beethoven symphonies and you prefer a particular subgenre of death metal? What if the client’s family is White, Black, Christian, and/or indigenous to the regions now known as the southwestern U.S., and yours is not? What if the person who brings your child client to therapy is the child’s aunt’s best friend, and she tells you that the child loves the LemonSheep brand toys, but you have never heard of LemonSheep and your favorite toy when you were a child was your dollhouse?

(Same answer. I structure my clients’ therapy programs in ways that I intend to be useful for them, not as if I were the client. For these examples, I would bring toy cars for the child’s session, invite both the dads into the session and use the word “dads” as a plural form that was never necessary in my own family, and make sure the patient has a fork for our dysphagia sessions. I do not play any music during speech therapy, but I could certainly use Beethoven symphonies as a topic the client can discuss during her fluency practice… or, well, why not, I can have the client play some parts of a symphony she likes on her phone, and then we can discuss it! If the client has religious obligations for Friday evenings, Sunday mornings, or some other specific time, I will schedule their therapy sessions at other times or on other days. I will believe the child’s aunt’s friend, accept the child’s aunt’s friend as a central person in this child’s life, and ask the child to tell me about LemonSheep toys. I will search online after the session to learn more, and I might buy some LemonSheep toys to have in my clinic or print something free about LemonSheep to use as a gameboard or coloring activity in our next session. I might tell the child about my dollhouse, as a way to share a bit about myself, but I would never drag my own dollhouse into the session with this child and insist that she must play with it.)

Easy enough? Is that what you already do? That is cross-cultural or cross-identity communication care. You do it already. And you, correctly and appropriately, do it with clients who are very similar to you in many ways, clients with whom you would say you share some but not all cultural or identity details, and also clients who differ from you in some, more, or many ways.

It is not difficult to notice or ask what a person likes or is comfortable with, believe their answer whether it would be your answer or not, and respect it or act on it. This is why you find a Batman coloring page for a child who says he likes Batman, or why you bring a range of coloring pages and let the child choose. This is why you ask clients to tell you about stories or movies they like, instead of insisting that they should do their language practice by discussing your favorite movie.

You do this all the time, with all your friends and with all your clients — or at least with most of them.

Why, then, do some clients feel complicated? Why do we spend so much time discussing the “complexities” of cross-cultural and culturally appropriate care? Why do we find some of the multi-cultural ideas from Box 18.3 or ASHA’s requirement that we are to integrate “each individual’s traditions, customs, values, and beliefs” into their service delivery (see Box 19.1, below) to be difficult sometimes? Why do we all harbor some “but what about” questions — some exceptions or limits that we might want to place on the traditions, customs, values, or beliefs we are willing to accept into our therapy sessions?

Many reasons. It might be related to our cross-cultural mindsets. It might be that we need to think a bit more about what bridges are and what bridge-building actually means. It might be that we need more specific cross-cultural information, or it might be that we need to try some different specific cross-cultural techniques and methods.

This module addresses all four of these topics, starting with ASHA’s general instructions and required mindsets for culturally responsive care.

ASHA’s Cultural Responsiveness Materials: General Instructions and Required Mindsets for Cross-Cultural Bridge-Building

ASHA’s materials on cultural responsiveness provide clear instructions for all clinical interactions: “Audiologists and speech-language pathologists (SLPs) practice in a manner that considers the impact of cultural variables as well as language exposure and acquisition on the individual and their family.” Clinicians are “responsible for providing culturally responsive and clinically competent services during all clinical interactions.”

Notice the reference to “all clinical interactions.” This requirement parallels ASHA’s (2017) requirement that we provide high-quality services to “all populations.”

All.

Once again, everything about culture, language, and identity applies to all our clients and all our practice, not to any subset of people. Cultural responsiveness, including high-quality cross-cultural bridge building, refers to and includes all clients, all potential clients, everyone we are serving, everyone we should be serving, and all our interactions with them.

And ASHA provides a long list of instructions, presented as the cross-cultural and bridge-building actions that we as professionals are required to take with each client and with every client. Read Box 19.1.

Box 19.1. General Instructions and Requirements for Bridge-Building: ASHA’s Required Actions for Culturally Responsive Clinical Service Delivery.*

“Demonstrating respect for each individual’s ability, age, culture, dialect, disability, ethnicity, gender, gender identity or expression, language, national/regional origin, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and veteran status

“Integrating each individual’s traditions, customs, values, and beliefs into service delivery

“Recognizing that assimilation and acculturation impact communication patterns during identification, assessment, treatment, and management of a disorder and/or difference

“Assessing and treating each person as an individual and responding to their unique needs, as opposed to anticipating cultural variables based on assumptions

“Identifying appropriate intervention and assessment strategies and materials that do not (a) violate the individual’s unique values and/or (b) create a chasm between the clinician, the individual, their community, and their support systems (e.g., family members)

“Assessing health literacy to support appropriate communication with individuals and their support systems so that information presented during assessment/treatment/counseling is provided in a health literate format

“Demonstrating cultural humility and sensitivity to be respectful of individuals’ cultural values when providing clinical services

“Referring to and/or consulting with other service providers with appropriate cultural and linguistic proficiency, including using” cultural informants, cultural brokers, interpreters, and/or translators.

*All bullets are complete direct quotes from ASHA’s material, except as marked at the end of the final bullet. ASHA’s list begins with three additional bullets about professional actions to be taken before interactions with clients that I have omitted from this list; see ASHA’s original.

What do you think of these requirements?

Are parts of it simple and obvious, as we discussed above? Of course we respect each individual’s age. We bring preschool toys for preschoolers and bring the Photos from the 1980s book for adults. Of course we integrate the client’s customs and treat each person as an individual. We bring forks for clients who use forks, we ask clients to tell us about their jobs or their hobbies, and we do not require Christian clients to come to therapy on Sunday mornings.

And yet, if we allow you to be honest, might you also have some lingering or more complicated questions?

What does “demonstrating respect for each individual’s… sexual orientation” actually require us to do during a speech therapy session? What about a clinician’s personal religious belief that homosexuality is a sin? Is she required to say “both your dads” to a child client, and find a picturebook that shows a family with two fathers to use in that child’s therapy, if she does not believe that gay men should be raising children?

What does “integrating each individual’s… beliefs into service delivery” require us to do? If the clinician is a woman, and the client makes it clear that he does not believe women should work outside the home, is she required to somehow integrate his belief into her work? What if the clinician is a darker-skinned woman, and the hospital patient comments to his visiting friend that he routinely questions the professional qualifications of all darker-skinned women?

What if a clinician views women in many Middle Eastern countries as repressed or abused? Imagine a clinician who sees a client’s veil as a symbol of a seriously problematic oppression, not as a pretty piece of fabric or as a positive expression of the client’s faith and family. This clinician might be very uncomfortable with, or even overtly angered by, the client’s husband’s assumption that he will be in the room during her therapy. Can that clinician at least ask him to wait in the waiting room?

What if we simply do not know? Are we really expected to integrate all the complexities of another person’s culture, ethnicity, religion, or socioeconomic status into our therapy when we simply do not know all the details? Don’t we run the risk of oversimplifying or mistaking an individual’s culture, ethnicity, religion, or socioeconomic needs in ways that could end up being insulting, stereotyping, rude, embarrassing, or just plain wrong?

Sometimes working with someone who is not me, who differs from me, is easy. I grab the toy cars and I start the session.

But sometimes, let’s be honest, sometimes it is not easy at all. Sometimes we are very aware that our starting point, on our side of the canyon, is nowhere near the client’s starting point, on their side of the canyon. Sometimes we look down at the space we are trying to cross and we see sharp rocks, raging waters, and other elements that we perceive as truly challenging to our personal, emotional, or professional safety. Sometimes you and your clients come from such different backgrounds, carrying such different assumptions, that it might seem almost impossible to imagine being in the same room with them, much less to design and implement a therapy program that centers their traditions, customs, values, or beliefs — maybe because you are aware that you do not know nearly enough about those traditions or customs, or maybe because you find those values or beliefs to be genuinely problematic.

How do we navigate the cross-cultural bridge-building in these cases?

There are several important parts to this answer, as summarized in Box 19.2.

Box 19.2. How to Build a Cross-Cultural Bridge: General Answers

Draw on everything you know.

Use your existing abilities as a good human being.

Think about the other dimensions.

Figure it out, keep learning, and do better next time.

First, as Box 19.2 starts with, we use everything we know. We draw on all the background information, all the history, all the models, all the standards, and all the metaphors. Everything from all 27 modules of this website can be relevant, as can much more information from a vast array of professional resources. We are highly educated professionals, with breadth requirements in our certification standards, for a reason.

Second, we draw on our abilities as clinicians and as human beings. You know how to help people. You are already a good friend, a good neighbor, and a good clinician. Use those abilities.

Third, we use all 14 continua from Morgan’s (1996) model of identities and from similar models. When you and a client seem to differ, take a moment to think about which dimensions have led you to draw that conclusion. Is it their race? If so, then think about the other 13 dimensions, because you and this person might be very similar in many ways, including your education level, socioeconomic status, age, sexuality, language, and other variables. Do they seem to differ from you in their language, their sexuality, their age, and also their race? Keep looking, because you have something in common; I can often start bridges to other people who are parents simply because we are both parents. And if nothing else, even if you are convinced that this person differs from you on every dimension you can think of, fall back on the obvious universals: You are both people, in the same room, at the same time, and you might have experienced the same weather on the same street before you came inside. You have something in common that can serve as the first brick in your cross-cultural bridge.

And finally, as facile as this might sound, the basic answer, general instruction, and required mindset could not be simpler, as shown at the bottom of Box 19.2: We figure it out. We do it. Our professional ethics value it and require it, so we figure it out. We value it, and we require it of ourselves, as individual clinicians, because our goal is not to provide high-quality, individualized services to some people and lower-quality, generic services to other people — so we figure out how to provide the best possible services to every client. That’s our job.

The items in Boxes 19.1 and 19.2 are requirements that apply to our work with all clients and with every client. There are no “unless” statements in ASHA’s requirements or in ASHA’s cultural responsiveness instructions. There are no “except if” statements. We are to respect every client’s cultures, identities, beliefs, abilities, and preferences, and we are to integrate every client’s traditions, customs, values, and beliefs into their therapy. ASHA’s required mindset, general instruction, and basic requirement are that we provide high-quality care to all populations, that we build an appropriate cross-cultural bridge to every client, and that we do so by respecting and integrating what every individual person needs us to respect and to integrate, because every client deserves the best possible individualized and individually-appropriate communication care.

So, yes, if they like toy cars or Beethoven symphonies, they will probably talk in their sessions about toy cars or Beethoven symphonies. And if their world includes two dads, or a synagogue, or volunteering for a certain political party, they will probably talk in your clinical sessions about dads, or synagogues, or political rallies. And yes, your related actions need to demonstrate your respect for their right to have these preferences, customs, and beliefs.

ASHA does not give us the option of saying “I can’t work with a person who believes X, because I believe Y,” or “I can’t work with a person with THAT identity or from THAT background, because of my personal identity or my background.” On the whole, ASHA does not even give us the option of saying “I will only serve as your clinician if you refrain from expressing your beliefs” (with some exceptions; we will come back to this). And ASHA’s explicit answer to “What if we don’t know"?” is that we are required to go learn: We have a “responsibility to achieve and maintain the highest level of professional competence and performance,” and we have a responsibility to “enhance and refine [our] professional competence and expertise through engagement in lifelong learning.” We do it. We figure it out, we improve as we go, and we do better next time. That’s our job.

Your Turn

Think about a recent client you perceived as both similar to you in many ways and also easy to work with. You were probably doing almost everything from Box 19.1 as you worked with that client. Read through Box 19.1 and identify some specific examples.

Discuss how you can use your actions with clients you perceive as similar to you as the base for how you work with clients you perceive as different from you. Given that no one is the same as you, given that all clients are similar to you in some ways and also different from you in some ways, and given that you will always need a bridge of some sort to reach any client, then what mindsets, knowledge, and skills do you already have that you could potentially use more often or in different ways?

We will expand in the rest of this module on most of ASHA’s requirements for culturally responsive therapy, as quoted in Box 19.1. The exceptions include ASHA’s reference to “assimilation and acculturation,” two terms that I tend to avoid and do not emphasize in this module. At one level, the ideas are uncontroversial: a person from Zambia who has lived in the U.S. for decades probably eats more pizza and hamburgers than a person newly arrived from Zambia eats, and by the fourth or fifth generation the members of this family probably eat about as much pizza and hamburgers as most other fourth- or fifth generation Americans eat. As Crain (2024) and others remind us, however, these terms are also related to assumptions and practices that can be unsupported, unsupportive, and straightforwardly cruel, including such abominations as the “Indian schools.” If we focus on respect, treating people as individuals, identifying appropriate goals and methods for each individual, working with cultural and personal humility and simple human kindness, and ASHA’s other requirements, I see no need to bring in such potentially fraught ideas as how “much” or how “well” any person or family has “adapted” to some arbitrarily selected “dominant” culture. But once again, we are each living our journeys and creating our own versions of our clinical practice. Do you find it useful to think in terms of terms cultural assimilation or acculturation with your clients?

This discussion emphasized ASHA’s requirement that we must provide high-quality, individualized, client-centered, culturally appropriate and identity-affirming communication care to all clients and to every client. What other reasons are there to work within this mindset and to seek this goal? If you are not ASHA-certified and not seeking to be, will you aim to provide the best possible individualized and culturally-appropriate care to each of your clients? Why or why not?

Reflecting on a Metaphor: What Does “Cross-Cultural Bridge-Building” Mean?

Another important part of the answer about how to build a cross-cultural therapeutic bridge to every client involves reflecting for a moment about what bridges are and about what bridge building actually means.

So take a minute, stand back, and give the bridge itself a bit of space in your mind.

Bridge building is a useful metaphor for many reasons. Part of the idea, of course, is that we need to connect to each of our clients.

But don’t stop there. The point of a bridge is not merely to connect.

The point of a bridge is to connect two points that are in different places. No one is the same as you. None of your clients are you. This obvious and silly starting point becomes more complex, and more serious, the more we think about it.

It’s okay that we differ from our clients. It’s okay that our clients differ from us. Of course they do, because of course they do, because they all do. And they all deserve our best possible services anyway.

Equally, bridge building recognizes that the two different points are not going to move. Bridge building does not mean lassoing the opposite bank and pulling it toward you like a cartoon character. Bridge building does not mean that the client on the other side of the canyon is trying to pull your side across or will somehow manage to make your side indistinguishable from their side. Bridges are not necessary when we could eliminate the distance instead, or if the gap is going to disappear tomorrow. Bridges are built because there is a space, in full recognition of the fact that there is a space and in full recognition of the fact that there will remain a space.

The bridge-building metaphor also implies, as we keep thinking about it, that the people on both sides of the river now have a safe way to go back and forth. Building a bridge does not include, much less require, that you fall into the river. The bridge prevents you from falling into the river! A bridge is a structure that allows people to navigate a crossing safely, in either direction and in both directions. Crossing a bridge to work with a client implies that we have safely avoided the rocky pitfalls that the differences between us might otherwise have represented, and it also implies that we will return safely to our own side 45 minutes later.

From a slightly different perspective, remember also that building a bridge does not include or require allowing yourself to be slugged in the stomach when you get to the other side. There is an enormous difference between a client who believes things you do not believe, or who has done things you would not have done, and a client whose actions during your therapy session are closer to slugging you in the stomach. Exceptions exist, of course, but most clients who differ from you have no actual desire or intent to hurt you. They are simply living their life on their side of the bridge, just as you are living your life on your side of the bridge. Their life is not the same as your life, because no one’s life is the same as your life. We accept this fact for every client, and we work with it, and we do not overinterpret mere differences as if they were actual threats to our safety.

If something genuinely and truly unacceptable does happen during your session with a particular person or a particular family, however, remember that being slugged in the stomach is not required. None of the standards or metaphors that shape cross-cultural service delivery require you to become the actual literal target of anything you perceive as an attack. Remove yourself from that situation (in a way that does not jeopardize your client’s safety) and ask someone you trust for help, if you ever do find yourself in this situation.

But if the only issue is that you and a client are merely on opposite sides of a canyon, no matter how large or complex that canyon might intitially seem, remember also that building a bridge to provide her with culturally and individually appropriate communication care is about providing her with communication care. You are not trying to re-shape a client’s culture, identity, religion, beliefs, or values to make them match yours. You are not required to change your culture, identity, routines, or preferences to match hers. The two of you as a dyad have not been tasked with solving any longstanding world conflicts, eliminating any widespread sociopolitical concerns, or writing a consensus statement about anything. The only reason you are together is to do a communication-care session together, focused on her speech, language, or related needs as a client. You are there to help her with her communication; she is there so you can help her with her communication.

We are required, in other words, to respect our clients’ cultures and identities in the context of their communication care plans and sessions. The requirement is not that we must integrate our clients’ traditions, customs, values, and beliefs into our own lives; the requirement is merely that we are to integrate their traditions, customs, values, and beliefs into their communication care plans and sessions.

This mindset, which might be phrased as “Remember why we are here,” might help, if you are still feeling uncomfortable about anything that Box 19.1 implies. We are not expected to rearrange canyon walls. We are not expected to become our clients. We are not expected to agree with our clients. We are not even required to like our clients.

Our individualized cross-cultural therapeutic bridges, in summary, do not merely help us to “connect” to our clients. They help us to navigate safely the real and probably permanent differences we have with all clients, and they do so toward a single and very specific purpose: to help us provide every client with the high-quality, respectful, individualized, cross-cultural communication care they deserve.

Your Turn

Discuss the instruction to “Remember why we are here” and the associated elements of bridge building, as discussed in this section. How does a clinical-care session (with its unequal power dynamics and its intent of helping only one of the two people) differ from a friendship or from your relationship with a relative?

General is Not Enough: Finding the Necessary and Detailed Information You Need to Support Your Cross-Cultural Therapeutic Bridge Building

ASHA’s requirement that we must integrate “each individual’s traditions, customs, values, and beliefs” into their therapy (Box 19.1) is part of why chapters exist with titles along the lines of “Working with African American families” or “Incorporating clients’ religious backgrounds in speech-language pathology.” This requirement is why you might previously have read or been asked to memorize purported factlets like “Native American cultures view the connections between persons, animals, and land as spiritual and communal, not possessive,” or “Asian cultures value older people’s wisdom and expect younger people to defer to their elders,” or even “People from Ethiopia eat curries and other stews, using pieces of injera held in their right hand.”

But if you have been reading along with us for a while, you also know that almost everything about this website has avoided or actively rejected such a reductionist approach to culture!

The knowledge that we need, if we want to build an effective cross-cultural therapeutic bridge to a single client, does not include vague generalizations that claim to describe over 4.5 billion people (the population of Asia) in a sentence or two. The out-group homogeneity bias is not our friend, and lists of stereotypes will never be part of the knowledge, skills, information, or abilities that support our clinical practice.

And yet: If I am trying to do dysphagia therapy with a client who has already told me that she and her family are Muslim, I need to know which foods which Islamic traditions allow and which foods which Islamic traditions do not allow. (I also need to know that Muslim refers to the people and Islam refers to the religion.) I will check the details with this person and this family, or start by asking what this client’s preferred foods are, but my knowledge will be critical — because my knowledge about cultures, religions, foods, and Islamic cultures is what allows me to know that I need to ask, allows me to understand this family’s answers, and allows me to act on what this family needs me to do as I give them examples of food textures that will be safe for their mother to eat.

If many families in my geographic area are Catholic, similarly, then I need to start with some reasonable knowledge about the days that a Catholic family probably reserves for attending religious services, so I can understand what they are telling me about scheduling and arrange sessions with them appropriately. I need to know if a 50-year-old businessman who grew up in Germany will probably sit on the floor in my office or would rather have a chair. If most of the women I have previously encountered in my personal and professional life have worn some version of a head scarf or veil, I need to know how to conduct a hearing screening with a woman whose ears are not covered by any fabric at all. I need to know that a White woman and a Black woman can be, yes, married to each other, and I need to know that the appropriate phrases will be “your wife” and “her wife,” as I speak to and about these clients this morning. If I am pulling bingo pages, word lists, or picture cards for any speech or language task, I need to know if Santa, a menorah, the 17th of May, and small round rice bowls are important to this client, irrelevant for this client, or offensive to this client.

And as these examples might have suggested, you are the only one who knows which parts of this kind of information are already obvious background knowledge for you, because of the journey your life has taken, and which parts of this information you still need to learn, to support your unique version of your cross-cultural bridge-building with your clients.

I cannot write the background information that you need, in other words, and no instructor can assign the background information that a whole class needs. And just as we cannot do cross-cultural therapy with a single client by trying to bring all the possibilities for all the cultures into the same room at the same time, it simply does not work for any resource to try to list all the information about all cultures. The only solution is for each of us, as individual professionals, to search for, evaluate, learn, and routinely update the specific information we need, given who we are, given our journeys through our lives, and given the clients we work with.

As a start, or as a step, and as the most detailed information I can provide for all of you, try spending an hour with one or more of the resources linked in Box 19.3. You will be drawn to some parts of it, and you will find yourself uninterested in other parts. That’s okay. Find the parts that you need or that interest you today. Read carefully, because many of these resources, as useful as they are, also reflect the problematic “Columns and Rows” or “Stereotypes to Memorize” kinds of information that I would still rather have us avoid. And commit to coming back later, as you work to develop and expand the background knowledge that you still need to develop and expand.

Also, I wish I did not have to say this, but I do: Protect yourself as you explore. The links in Box 19.3 are mostly professional resources, positively framed, and should be safe. But if you do an internet search for the name of any particular cultural group so you can help clients from that group, you are going to find some very problematic examples, scams, lies, misinterpretations, and distinctly negative material. If you search with only the purest of intents for intersectionalities such as “rural Korean women,” the internet is going to show you some terrible stuff. Protect yourself from all of it. Do not open or download anything until you have verified the source, do not spend any money on anything you have not checked thoroughly, use everything you learn always and only to help your clients, and do your best to stop the proliferation online of anything you can help to stop.

Box 19.3. Selected Possible Resources for Specific Background Information about Cultures, Identities, and Intersectionalities

The WISE Collection, at Ithaca University: https://www.ithaca.edu/wise-working-improve-schools-and-education

The WISE collection is among the most comprehensive cultural resources I am aware of. Despite the name, its material extends well beyond schools and education. Use the vertical menu bar along its left side to find information about African American, Arab American, and many other cultures.

ASHA’s Resources about Culture: https://www.asha.org/practice/multicultural/

Most of the information provided by ASHA consists of models, standards, and philosophies, rather than specific details about individual cultures or the background information about cultures or identities that we are currently seeking, but you may find parts of this webpage useful. We will refer to parts of it in Module 20, when we consider cross-linguistic and multi-linguistic practice details.

The first edition of Dr. Battle’s classic book broke new ground for speech-language pathology. The fourth edition is getting old, but it still provides among the best chapter-by-chapter information about individual cultures (of the type that I tend to resist but that we are currently discussing and seeking). If you cannot access the book through a library, you can probably buy a used print copy relatively inexpensively.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: https://www.hhs.gov/programs/index.html

The Department of Health and Human Services has traditionally provided a wide range of information through its CLAS Standards pages and elsewhere. Start with some of these links and explore.

Speech-Language Associations from Around the World

Use this list provided by ASHA to access parallel websites from other countries. Your web browser should translate these sites to English, if you do not know that country’s language.

International Speciality Associations

Search for “international association” with the name of any condition or ability you are interested in, to find information intended for a range of people from different cultural backgrounds. (Evaluate the materials you find very critically; their quality varies widely.) Here are two good examples.

Learn from Books Intended for Children

Books intended to explain other people, cultures, or countries to children can be wonderful, accessible resources for all of us! Try the links below, or ask the children’s librarian at your local public library to recommend their favorite books about any identity, culture, language, or intersectionality that you are trying to learn about. Be careful of the culturally pre-competent “heroes and holidays” problem (Lee, Menkart, & Okazawa-Rey, 1997) in children’s books; try to find books about regular people living regular lives.

“Parents of” and “Living with” and “Advocating for” websites, social media sites, or videos

Search for associations or groups that exist to provide self-help, family support, or community support for people living with any cultural or other identity you are trying to learn about. Search explicitly for intersectionalities (use web searches of the form “living as a Latina with physical disabilities” or “supporting my gay Black teen,” or search within any website devoted to one culture or identity for information other cultures or identities). Here are a few examples; there are many more.

https://www.downs-syndrome.org.uk/about-downs-syndrome/lifes-journey/

https://keepitsacred.itcmi.org/traditional-foods-resource-guide/

Learn from Literature and the Arts

Explore some completely different resources. Learn more about more people. Here are a few examples; there are many more.

https://www.loc.gov/research-centers/american-folklife-center/about-this-research-center/

https://www.loc.gov/programs/veterans-history-project/about-this-program/

Find a Real One

My final suggestion, if you are trying to learn about any cultural or identity-based aspect of real people, is to find a real example. Instead of reading about the role of religion for people from a certain background, for example, read the real website of a real mosque, synagogue, or church in your area. Instead of reading about the intersection of race and homelessness on a website, go volunteer at your county’s shelter and talk to people. Instead of trying to read about clothing or hairstyles, go shop in a section of town you might never have otherwise approached. If you have a classmate or a colleague whose familial or personal background seems to differ noticeably from yours, offer to buy them lunch and ask if they would be willing to tell you stories about how they grew up. (Be sure to take your acceptance, respect, humility, and willingness to learn with you!)

Your Turn

Which resources linked from Box 19.3 did you explore? What did you learn? What did you enjoy? How will that information help you build a bridge to a client?

What other good resources did you find, as you searched, that were not linked from Box 19.3? Share your suggestions with your colleagues or classmates, and ask what they found that they can recommend.

What terrible, biased, bigoted, and unhelpful online scams or other problematic material did you find, as you searched? Did being exposed to that kind of website or video provide you with any useful knowledge or insight in any way?

Think about our three organizational models from Module 2: Hofstede’s (2011) six major dimensions for groups, Morgan’s (1996) model of identities, and our 16 Questions matrix. Using the ideas from those models to structure your search, spend some more time with the resources in Box 19.3.

Search within any of the resources listed in Box 19.3 for information about your own cultures, identities, and intersectionalities. If you somehow had lost all your background knowledge about yourself, would the information you found be enough to help you understand your life, circumstances, and needs? Reflect on this issue for the situations in which you are searching to learn about a culture or a combination of identies that you truly know very little about. How else can you find or learn the specific information you need, to build a specific bridge to a specific person?

Twelve Specific Cross-Cultural Therapeutic Methods

Next and final step.

You have all the background information. You understand ASHA’s requirements. You want to provide personalized, culturally appropriate, and individually affirming communication care for every client you see. You understand that your job is to build and use a bridge that facilitates communication care for your client. You have learned at least some initial information about the cultures that might be the most relevant to your caseload in your area, or you have spent a minute reading the WISE resources about what you believe to be the relevant cultures and identities for a client who is on your schedule for tomorrow.

How, exactly, will you then build and use the best possible cross-cultural therapeutic bridge and conduct the best possible cross-cultural assessment and intervention with a client?

Here are a dozen possibilities, listed in Box 19.4 and then described in greater detail below. You will notice some overlap among these ideas, and you will also need to use your background knowledge and your clinical discretion with all of them; none of these options is a required rule. If your client who needs pureed textures would show up with steak and salad if you allowed him to “bring his own,” or if being asked to bring something to speech therapy would create an expense or complication for the family, then obviously the first possibility, to have clients bring their own, might not be a good fit. But you are a wonderful, kind, creative, client-centered clinician. Read these ideas with an open mind, searching for more times when you could try more of them — or at least try more of the first eleven.

Box 19.4. Twelve Techniques and Methods for High-Quality Cross-Cultural Communication Care

Have clients bring their own (and then you bring others like it next time).

Greet the client with a specific question.

Verbalize the universal and the cultural as part of writing every goal.

Build a multi-cultural materials room, bring cross-cultural options to the session, and allow the client to choose.

Use personalized electronic stimuli (carefully).

Focus on the “A” Words: Ask, Act, Accept, Alter, Adapt, Adjust, Accommodate.

Structure therapy around the client’s entire community of care (Watermeyer, 2020).

Approach all client care as cultural adaptation research (Muñoz, 2017).

Consult and collaborate with more cultural informants and cultural brokers.

Practice trauma-informed care and hope-informed care.

Apply universal approaches as specific techniques.

Use a specific, appropriate, ethical referral to another clinician.

1. Have Clients Bring Their Own (and Then You Bring Others Like It Next Time)

Start with this one: Have the client bring their own. Do you need a culturally-appropriate toy to play with, an identity-appropriate book to discuss, or something for the client to eat or drink during your session that will be familiar and comforting to them? Whatever it is you need, have the client bring their own. One way to match what clients need is to allow them to show us, rather than presuming that we could possibly guess ahead of time what will be a good fit for another person.

Bringing their own conversational partner often works well, too, as a variation on the same “bring their own” idea. Instead of assuming that we are the best possible conversational partner for a client, we can ask them to bring a friend or a family member, positioning ourselves as a communication strategies coach and allowing them to serve as their own experts about their culture, values, beliefs, religion, and so on.

We can also learn from what we see in the first few sessions; believe that the client needs, wants, and likes these things; and try to bring something similar in later sessions, to take the burden of providing supplies back off the client and to introduce some necessary variety into your sessions.

2. Greet the Client with a Specific Question

Our clients and their families show us many things at the very beginning of every session that can serve as building blocks in our cross-cultural bridges, if only we make the effort to notice. They are chatting about something in the waiting room or looking at something on their phone in the waiting room, or they get up from the waiting room chair very slowly. They have a jeweled pin on their lapel or they are wearing red shoes. The client or her parent or her grown child is wearing a uniform shirt from work. There is now a third IV pole next to the adult’s hospital bed, or the child is at a different table when you enter their classroom. If nothing else, they have lived somewhere between a few hours and a few weeks of their own life since you saw them last.

To start every session, notice any of this and ask a specific question about it. With the same kindness and care in your voice and in your smile that you would use with your very favorite people in the whole world, greet your client with a specific comment (“Something fun on your phone?”, “No rush, are your knees sore today?”, or “Looks like they brought in some more medicines?”) instead of with the generic “How are you today?” And keep going: Make the effort to create a full conversation about this topic. Ask follow-up questions, and keep accepting the client’s answers. And if the thing you have noticed is something that differs from you or that you do not have the cultural background to understand, then ask, with kindness, acceptance, and cultural humility: “The fabric in your scarf is so pretty! Scarf, would you call it a scarf, I’m sorry I don’t know the right word.” (Now you do. Use the word next week. It will become a brick in your cross-cultural bridge.)

3. Verbalize the Universal and the Cultural as Part of Writing Every Goal

Before we develop any intervention plan for any client, we need to be able to identify the relevant human universals and also the relevant specifics from the client’s cultural or identity-related context. This principle shapes all our language-specific goals (e.g., which phonemes, morphemes, syntactic structures, and semantic items to teach, and why), as Module 20 addresses in detail. It is also critical for everything else about a client’s speech, voice, literacy, or communication that we might be proposing to change. Taking the time to identify and verbalize both the underlying human universal and also the relevant individual specific details for every goal helps to ensure that we are not teaching our own familiar specific details as if they were a human universal or as if they represented a relevant specific detail for another person.

Consider the following fragments of example therapy goals. Which human universals do each of these actions represent? How are those universals realized in the specific communities you have encountered?

… will initiate communicative interactions…

… will exhibit turn-taking and topic-maintenance behaviors in conversation…

… will demonstrate reduced vocal loudness…

… will use 2- to 3-word utterances to express individual wants and needs…

… will describe the function of common household items to facilitate naming of those items…

Do you see some of the important issues here?

All conversations are intitiated by someone, and all conversations include turns from two or more participants, to start with the first examples, but many details are culturally determined, represent different places along Hofstede’s (2011) dimensions, and are influenced by Morgan’s (1996) identity dimensions (e.g., age, gender, education). Who is allowed to initiate a conversation with whom? How exactly are conversations initiated between which partners and under which circumstances? The key here is to be sure you understand those details from the client’s world and plan to teach the client to implement the details that will be appropriate for their life, not for yours. We do so by stating the universal and separately stating the specific, as a technique that helps us be sure we are not conflating the two or teaching our own specific as if it were a universal.

All speakers use a range of quieter to louder productions, to take another example, but why would we be targeting reduced vocal loudness, and what will that change create or imply for this client? Does loudness convey authority, power, masculinity, lack of control, self-actualization, or a risk factor for vocal nodules, in this person’s world? What are we doing to a person’s roles in his family or his work group, or to his hard-fought efforts to be perceived the way he wants to be perceived, if we ask him to speak more quietly? The universal, which we must be able to state before we write any goals about vocal loudness, is that people can produce voice using a range of loudnesses. The specific, which we also must be able to state before we write any goal for any other person, must incorporate how loudness is used and interpreted in that client’s world.

And your professional assumption in teaching clients to use a functional-description strategy as a solution to what you see as their word-finding difficulties is probably that the description substitutes for the name and/or will facilitiate retrieval of the name — but let’s divide between the universal and the specific here, too. Universally, nouns can be named and functions can be described. But specifically, silence if you cannot be succinct might be important to a client, and taking up other people’s time with a tangential stream of round-about words might be perceived as self-centered, rude, or simply inappropriate, not as a reasonable communicative strategy. A man who worked outdoors to provide for his family may know neither the name nor the function of items that you assume to be “common household objects,” or the entire family might consider them women’s things that he should not be expected to discuss even if he does know. We cannot mistake the universal (names exist and functions can be described) for the specific.

The basic point here is that cross-cultural communication care requires us to be able to specify why we are targeting any goal generally (the human universal that this category of actions represents, given the human universal that people use speech and/or language to communicate with each other) and also to specify precisely what we are seeking to change and why for any individual. This relatively brief action on our part, the technique of verbalizing the human universal and also asking the client or the family about how they want to realize their specific version of that universal, is a crucial and critical feature of cross-cultural clinical practice.

4. Build a Multi-Cultural Materials Room, Bring Cross-Cultural Options to the Session, and Allow the Client to Choose

You need materials or clinical stimuli for your therapy session: toys, picture cards, word lists, sentences, story starters, reading passages, etc. If your client is not bringing their own, or if your professional expertise is an important part of identifying them, then plan to take more than you need and select a subset with the client during your session.

You probably do something like this already. You might take the farm toys and also the kitchen toys so the child can choose, or you might bring a whole magazine and have your adult client select one article to work with. As a cross-cultural bridge-building technique, we do the same thing more often and more conscientiously. Think about culturally-influenced variety as you stock your materials room, and then select options for each session by thinking about the client’s possible assumptions and experiences, not yours.

If your community includes families from Hmong, Mongolian, and Mexican backgrounds, for example, you can easily build a materials cabinet by picking up flyers from the smaller local grocery stores and by collecting handouts from your public library that are intended for those communities. Stop in to any community agency that serves veterans or serves tribal elders or serves foster families, and pick up their flyers to use as conversational materials during speech therapy. Given that people have a range of skin tones, buy some FisherPrice people with a range of skin tones. Given that people’s bodies differ, populate your toy box with some smaller dolls, some rounder dolls, and some of the many available dolls that use wheelchairs. Build your library of books by selecting international wordless picturebooks, which show a range of culturally influenced artistic styles and which do not require familiarity with any language or dialect. Curate a library for yourself of books that are either for or about people with a range of physical and cognitive abilities, or select books about specific cultural backgrounds from a source such as the Social Justice Books project.

Then, as you select things from your collections to take to an individual session, take a range of options, including some that you are guessing might match the client’s experiences or that reflect your best and most respectful attempts to consider the client’s places, not your places, along the many relevant continua [i.e., think in terms of Morgan’s (1996) identity dimensions, or think in terms of ideas about which foods, clothing, sports, or other activities you think you know might feel familiar to this client]. The client will be drawn to some of them more than others, for any number of reasons. Use those materials in your session, and use what you have learned when you select your range of materials next week.

5. Use Personalized Electronic Stimuli (Carefully)

If you use electronic stimuli during your session, rather than physical dolls and magazines, you have a truly infinite set of personalized stimuli at your fingertips, including those that are a perfect match for your individual client’s specific cultures, identities, traditions, and preferences. The only trick is to make sure we are using good materials, not stereotypes, not websites that a child’s family has prohibited, and certainly not any problematic AI-generated material.

For conversation-level practice in language, fluency, or voice, for example, a child’s parent can show you which media, pop culture, sports, or music websites the child is allowed to access. With parental oversight, adolescents can show you which sites or social media feeds they follow. Older children and adolescents can probably access their schoolwork on their phones, if anything from school interests them or if you want to use curriculum-based materials. Adult clients, similarly, can select material from the news or entertainment sources that they tend to follow, or they can use their phones to access information from work, their photographs, their calendar, and many other personal materials that reflect their lives perfectly, all of which can serve as the basis for communication care sessions that center their cultures, identities, traditions, and preferences.

For some clients from some backgrounds, you might also be aware of speech-therapy websites that provide materials tailored to groups such as persons from Latin America or African American children. Be careful that such materials are not perpetuating stereotypes; they need to be correct matches to your client’s background, experiences, and identities, not problematic or incorrect overgeneralizations. If they are a good fit, they can be a useful part of your sessions, and they might be worth seeking out.

Beyond currently existing materials, or when you need more specific stimuli to address a certain speech or language target, we can also use artificial intelligence systems to produce word lists or picture stimuli that are appropriate for a specific speech or language target and that are tailored narrowly to a single client’s specific cultures, traditions, or preferences. Simple prompts such as the following, and many variations, can be used repeatedly during a session, because they generate stimuli almost instantly.

show me 12 English words about animals that all start with an S-blend, are related to Brazil, and are appropriate for a child

show me 12 phrases in English that all include a regular simple-past verb, are about the Diné people, and are kind and nice, and also show me the Spanish translations of those phrases

show me 12 simple line drawings of words related to Korean food or cooking

I tend to request “kind” words or words that are “appropriate for a child” almost always; requesting “adult” examples or “a range of examples” can produce violent or inappropriately sexual options. With most clients, I am also very careful to make sure I see everything on the screen before I let them see or share the words with them. If your prompt requests 12 words, as in these examples, you can drop two inappropriate ones and still have the 10 that you might be looking for.

Cultural humility and centering your client’s preferences are also necessary here, as are your simple kindness and gentle curiosity about the client’s world. Your goal is not to limit the client to a stereotype; we do not say “You look Korean, so let’s focus on Korean cooking.” Your goal is to structure each client’s therapy sessions around topics that matter to them, using examples of those topics that feel familiar to them and allowing them to help you generate the prompts you will enter into your AI. Start with a couple possible categories (“We need some words to work with today — would you like to do foods or sports?”), and then build on the client’s answers (“Food, okay, perfect; should we do Korean foods or something else?”, with a Korean American client, or “Sports, cool, what sports does your family like?”, with almost anyone). When you have exhausted what you can do with those words, use something that came up in the conversation or ask the client where to go next, creating a sequence of prompts that reflects your client’s interests, not your choices:

show me 12 simple line drawings of words related to Korean food or cooking

show me 12 more simple line drawings of words related to Korean foods for the Lunar New Year

show me 12 short phrases that include words about the Lunar New Year as celebrated by Korean Americans in Chicago

More complex prompts, including prompts requesting images, currently take a minute or two for AI systems to manage — although this technological limitation might not be true any more by the time you are reading this module! One option is to develop the prompt with the client and then use the wait time to practice something else or to play a guessing game about what the result might include that will, on its own, provide the client with more practice. Alternatively, if the minute or so would be inappropriate downtime for your client, you can create personalized electronic materials ahead of time and save them or print them.

Working ahead of time means that you will have to take your best guess about the client’s preferences, rather than following their lead, but working ahead of time also allows you to catch and correct the errors that AI systems will generate. Some errors in AI output, as you have no doubt seen for yourself, are crucial and fatal errors that should lead you to delete the output immediately, especially in generated images. Most AI errors, however, are arguably manageable, as balanced against the advantages of using personalized stimuli for each client. Look carefully at the images below, for example; they include several problems from our point of view, but from the client’s point of view they might be creative, meaningful, and also centered on their worlds and their interests.

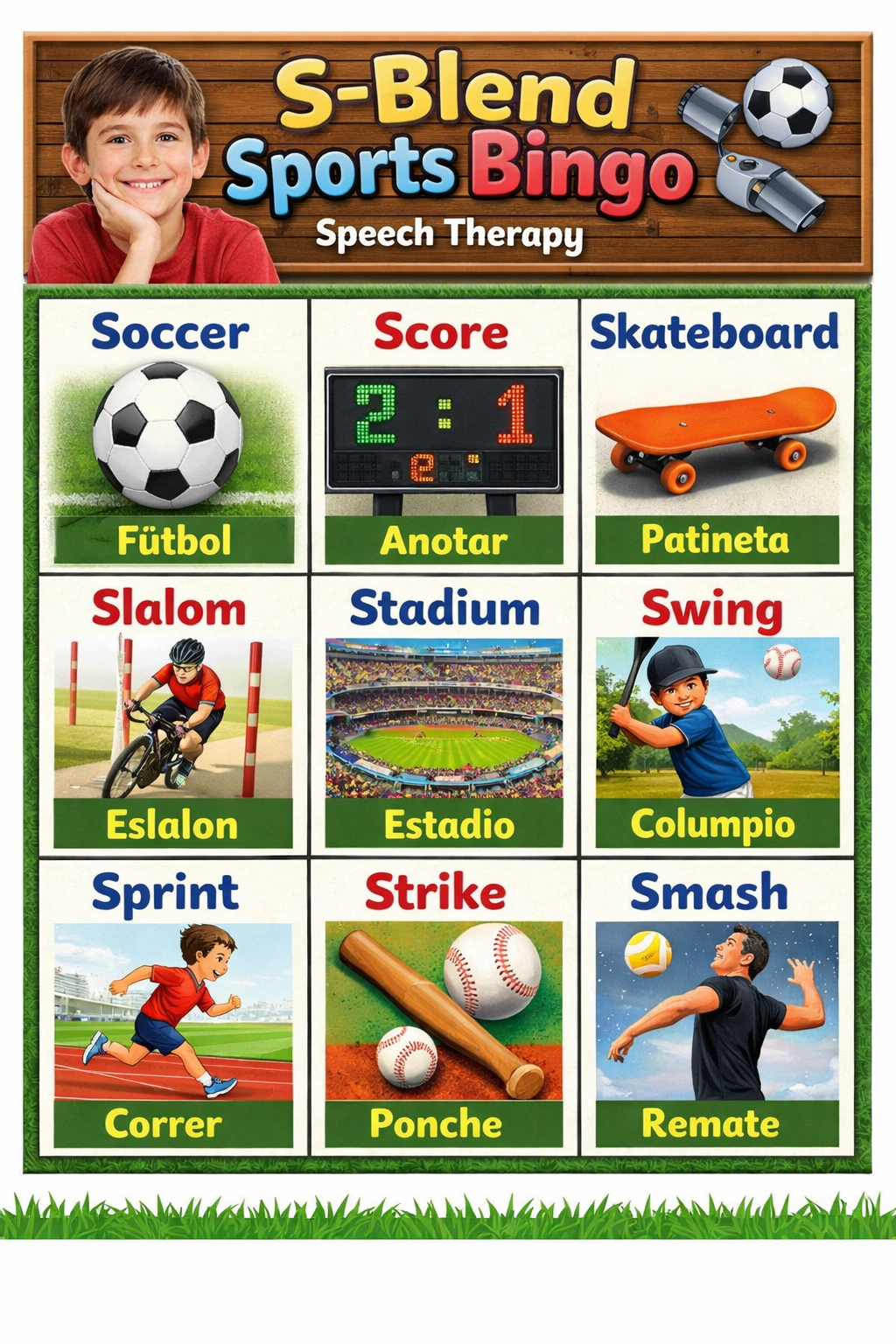

The first image below was created by ChatGPT in response to the following prompt: Create a bingo board for speech therapy in English with a 9 year old boy. Use words that start with S-blends and that are about sports played in Mexico. Put a picture of each word and put the Spanish translation of each word. Errors include the inclusion of the word “soccer,” which does not start with an S-blend but which could be a reasonable review item or easy item for some clients; the made-up string “fütbol,” which does not exist, instead of the correct Spanish “fútbol”; and the unclear imagery at the top right and meaningless imagery in the scoreboard. Would you use this image with a client? If you had generated it ahead of time, it would only take a couple minutes to have ChatGPT correct the errors. You might also either remove the purely decorative image of the child or change it to a child who shared more of your client’s visual characteristics.

The second image below was created by ChatGPT in response to the following prompt: Create a page we can use in aphasia therapy to work on verbs. The page should show six pictures of an African American business woman doing something different in an office. ChatGPT did not use the visual features of typical speech therapy materials this time, the woman’s blouse is strangely neither tied nor stitched, and the visual noise on that whiteboard is imperfect, but otherwise this image strikes me as useful, as is, for therapy with a client who is or was an African American business woman — and it is certainly preferable to using images of White men to work on office-based verbs or phrases with an African American woman.

6. Focus on the “A” Words: Ask, Act, Accept, Alter, Adapt, Adjust, Accommodate

An amazing number of “A” words provide outstanding advice for building cross-cultural therapeutic bridges and providing cross-culturally appropriate individualized therapy.

Ask the client what they need, want, expect, assume, value, or prefer, whenever you have any smaller or larger decision to make about any aspect of therapy. Act on their requests.

Accept that their values, beliefs, choices, actions, and answers are as true for them as yours would be for you. Act on your awareness of their assumptions and preferences.

Plan to alter your goals, methods, stimuli, and actions to make them fit each client. Think in terms of starting with your basic professional therapeutic methods and then altering or tailoring those methods to fit each single individual. A basic pair of pants from a basic store can be an acceptable starting point for many people, but it also will not fit any one person correctly until it has been hemmed, taken in at the waist, and/or let out ever so slightly at the hip.

Adapt your goals, methods, stimuli, and actions to your client’s background; adjust to what is happening during your session and to whatever your client needs. Our role is to recognize where our clients are along the many relevant cultural, identity, and other personal dimensions and then to build bridges toward wherever they are. Making the adaptations or adjustments that build kind, supportive, cross-cultural, interpersonal therapeutic bridges is our responsibility, as the professionals, not our clients’ responsibility.

Accommodations in educational and other settings help learners to access necessary content, and express their understanding of that content, in ways that fit their specific needs. Providing Braille materials or large-print materials to a few of the people in a science class are classic examples, as is allowing some students to take the written science test alone in a quiet room. The underlying goal of ensuring that everyone understands about volcanoes does not change, but how exactly that underlying goal is explained, addressed, sought, and met for any one person often needs to change. Cross-culturally, we use the same idea: The underlying goal (the universal) of being able to produce the combinations of phonemes that a certain dialect uses or to understand complex sentence structures does not change, but how exactly that underlying goal will be explained, addressed, sought, and met (the specifics) must change for each individual.

7. Structure Therapy Around the Client’s Entire Community of Care (Watermeyer, 2020)

Watermeyer’s (2020) article about communities of care for adults with aphasia in a multi-cultural environment provides an excellent specific and useful model for all cross-cultural care. The model emphasizes the importance of families, friends, paid and unpaid caregivers, community members, volunteers, and social networks. The term “community of care” emphasizes that these people and networks exist not only as the client’s background or context but also, importantly, as part of the care that the client can and should receive currently and in the future. The care that these different people provide will differ, obviously; a volunteer from the church who drops off a meal once a week has different responsibilities than a live-in health aide has, and both have different responsibilities from those of the client’s grown daughter who lives across the country or those of the person who runs the children’s story hour at the library. But every part of the client’s community of care is important, and our interventions are most effective when we recognize everyone and everything the client’s community of care includes.

Thinking in Watermeyer’s terms, then, cross-cultural care requires identifying and then addressing the specific relevant people, systems, and social networks for each client’s entire community of care. By focusing on these individuals, we are recognizing, respecting, and responding to the client and to the cultural and individual circumstances of the client’s world. From there, we can design communication interventions and supports that address each of the persons and each of the networks that each client needs, has, and deserves.

If you do not know where else to start, then, with a client who feels very different from you, try planning a 12-week therapeutic sequence that focuses on their community of care. Start by addressing your client’s communication abilities and needs with their closest parent or partner, their children or siblings, or the other people they identify as the most important to them. Then add discussions or strategies to address their communication with friends, neighbors, unpaid personal or medical caregivers, paid personal or medical caregivers, their religious or community groups, the volunteers they interact with, and the businesses or schools they interact with. This list can obviously be changed to fit any individual’s circumstances and needs; that’s exactly the point of cross-cultural therapeutic methods.

8. Approach All Client Care as Cultural Adaptation Research (Muñoz, 2017)

Muñoz (2017) described several approaches to the research-based development of culturally appropriate interventions. Much of her paper then focuses on the “heuristic model,” which requires researchers or clinicians to work through the following sequence.

Gather information about the client’s culture, identity, language, abilities, and needs.

Select an existing, evidence-based intervention approach that seems a reasonable fit for the client’s abilities and needs. Make preliminary adaptations to it, to make it fit the client’s culture, identity, and language.

Test the effectiveness and efficiency of the adapted intervention.

Now using all the information that is now available, refine the adaptations. Repeat this sequence.

Muñoz did not use the words “universal” and “specific,” as Leininger would have, but do you see that the ideas are very similar? Communication and language are universal; languages and people are specific. Muñoz’s model also reminds me of simple single-subject experimental design: gather some data, introduce a reasoned and reasonable intervention that we have reason to believe will be helpful, gather some more data and make informed decisions about the effects of the intervention, then continue with a sequence of other data-based changes.

Muñoz’s emphasis on starting from existing evidence-based therapy methods is important. Every client is individual and special, but we are not starting from scratch every time. You might not have worked with a client from Country X before, and you probably will not be able to find a randomized controlled trial to read that studied 400 clients who had the same cultural and identity intersectionalities that your current client has. But you do have a professional knowledge base! So, as Muñoz emphasizes, you can start with our profession’s research literature and other evidence, with your knowledge of evidence-based practices, and also with your awareness that cultural, linguistic, and identity-based details will need to be changed to make any treatment appropriate for any single client. The rest is seeking the specific information you need (see our Box 19.3), combined with cultural humility, kindness, and person-centered attempts to recognize, respect, and respond to our clients’ individual needs using a sequence of data-based adaptations.

9. Consult and Collaborate with More Cultural Informants and Cultural Brokers

Cultural informants are consultants who provide an outsider with information about a culture (Spradley & McCurdy, 1972). Cultural brokers are collaborators who actively facilitate interactions between members of two cultures. A cultural broker, like a real estate broker, understands the assumptions and the needs of two relevant groups and also brings additional expertise that allows them to explain to both people what the other person is probably assuming, expecting, perceiving, and seeking during a series of interactions.

The importance of cultural brokers has long been emphasized in education for African American children (see Gentemann & Whitehead, 1983), because of the potential for cultural differences between African American families and the family backgrounds of most teachers and school administrators in the U.S. Cultural brokers are also important to anthropology research, international business, and many parts of healthcare (see Jezewski, 1995). Both cultural informants and cultural brokers can be important partners and collaborators in our cross-cultural communication care, and my basic advice here is to think broadly about who might be able to serve in these roles for you and to work with more of them more often.

If your client’s family is from a country you know relatively little about, for example, you might be able to provide generic and minimally adequate therapy for them without seeking out too much more information. To provide the best possible individualized care, however, you could seek an informant by calling a faculty member at a college near you who has expertise about that region of the world. They or one of their students might be not only willing but actually very excited to speak with you about the country’s history, or at least to point you toward some good reference material. Similarly, you might consult with someone who has expertise about parts of a client’s identity through a local agency that organizes adaptive sports for people with Down syndrome, at a religious institution in your town, at your county’s council for assistance to the aging, or through a local PFLAG group. Thinking in terms of the rows rather than the columns, you might also seek out a local expert on the arts-based, culinary, vocational, or other aspects of human life, to ask for their expertise about those aspects of a client’s cultures or identies. If your school has a social studies teacher or a Spanish teacher or a world-history teacher or an art-history teacher or a music teacher, seek out that person’s professional cultural expertise. And take the time to develop friendships with a wide range of colleagues whose personal experiences differ from yours; as we address in Module 27, our ability to learn as adults is linked to our ability to surround ourselves with people we trust to give us information and advice.

Finding appropriate cultural brokers can be more difficult than finding a quick consultant or informant, depending on your work setting. Recognizing the resources that are available to us often becomes much easier, however, after we have recognized our need for them and committed ourselves to seeking, valuing, respecting, and acting on other people’s knowledge and experiences. If your hospital system or your school district has a care coordination office, a diversity office, a chaplain, a family-support office, or any such set of professionals, for example, call them often. If you have found your school’s social studies teacher or Spanish teacher or world-history teacher or art-history teacher or music teacher, see if you two could somehow collaborate in ways that will allow them to serve as a cultural broker for you with a child or a family, based on their expertise about the cultural bases of languages and history and art, while you share your communication-based expertise with them. Interpreters and translators, whose expertise often extends well beyond the languages they bridge, can also serve as excellent cultural brokers, if we are paying them appropriately as the professionals they are to do this double work (see more in Module 20 about working with interpreters and translators).

Clients and family members can also serve as their own cultural brokers, in some situations, but do be aware that most people are not experts in explaining their culture’s unspoken assumptions and complex historical dynamics to members of other cultures. Clients and family members also must be allowed to be the recipients of care, not expected to become the providers of our necessary professional education. We do not expect clients and families to explain their culture to us while they are busy learning, healing, grieving, worrying about finances, focusing on their family member’s needs, or simply living their own lives. Ask them, observe them, believe them, and allow them to tell you what they need and want to tell you, yes, but if you need more help than your clients should reasonably be expected to give, find someone else to help you.

10. Practice Trauma-Informed Care and Hope-Informed Care

Trauma is complicated and multi-faceted, but the term refers generally to ongoing difficulties in individuals’ physical, mental, social, emotional, educational, vocational, or spiritual functioning or well-being that are related to previous events or circumstances that the person experienced as physically or emotionally harmful, life threatening, and/or out of the individual’s control (see the SAMHSA website). Trauma is important during our individual communication care sessions because it influences how individuals respond to challenges, frustrations, new information, new situations, and feedback from even the gentlest and most well-meaning clinician.

Remember also that, while trauma can and does occur to people of all cultures, backgrounds, and identities, it also occurs disproportionately in the U.S. among some recognizable groups and subgroups of people (as we addressed in our Module 10). Thus, in providing cross-cultural communication care, we are especially aware of the potential for trauma in people from the racial, ethnic, and personal backgrounds that have historically been marginalized in the U.S. (Andersen & Blosnich 2013; Merrick et al. 2018), especially when we ourselves do not share an individual client’s such identities. Trauma is known to be relatively more likely for people whose identities fall toward the “oppressed” ends of the continua represented in Morgan’s (1996) model of identities and for people whose multiple cultural or identity-based characteristics intersect or compound each other in specific ways (Crenshaw, 1989). Trauma is related to the social determinants of health and is more likely as the number of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) increases (as Module 10 also discussed). Ongoing trauma is also common for people who served in military combat, for people who experienced largescale natural or human-caused disasters, and for people who have survived physical accidents, regardless of when those experiences occurred or how much time has passed.

That’s a lot of people.

Indeed, because trauma is so common, the principles of trauma-informed care start by emphasizing that institutions, facilities, and organizations should interact with all clients and all families in ways that are specifically designed to feel safer and more predictable to everyone. The care process itself should not re-traumatize clients or families (see Menschner & Maul, 2016).

As individual clinicians, we can also seek to incorporate our knowledge of trauma as we provide cross-cultural communication care with individuals, usually in one or both of two ways.

The first options stem from the approaches and techniques known as trauma-informed care. You are probably incorporating parts of these ideas already, because they overlap with other best practices and clinical recommendations. Trauma-informed care includes, for example, seeking to create clinical spaces and interactions that you, your entire staff, and all your clients perceive as physically and emotionally safe, trustworthy, predictable, understandable, collaborative, and empowering for everyone. Specific trauma-informed recommendations include all of the following, for all our interactions with all clients and families and especially for our interactions when we perceive that the client differs from us along cultural and identity dimensions.

Warn clients that some of the questions you need to ask are personal, and tell them ahead of time that they can skip any question they need to skip, during interviews and on written forms.

Always explain, ask permission, and offer alternatives before you touch anyone.

Never use toys, videos, or other materials that make sudden loud noises or that include or depict guns, bombs, physical restraints, or other obvious violence.

Be specifically prepared for emotional reactions that differ from yours, and be ready to say “I’m sorry, this is obviously hard for you, what do you need?” The client’s or family member’s anger, frustration, or sadness is never “out of proportion” or “unnecessary”; the issue is that they are responding to the combination of their inner trauma and the external aspects of the situation, whereas you are aware only of the external aspects. Say, “I’m sorry, this is obviously hard for you, what do you need?”, then do your very best to agree with the client and to provide something as close to what they ask for as you possibly can.

A second set of specific techniques for cross-cultural care stems from research showing that the effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs, Module 10) can be mitigated by several protective factors. Known as HOPE-informed care (Sege & Brown, 2017), making lemonade (Counts et al., 2017), and other similarly friendly names, these positively framed techniques focus on helping all clients to develop circumstances including the following (all of which are known to mitigate the negative effects of ACEs):

Being in nurturing, supportive relationships

Living, developing, playing, and learning in safe, stable, protective, and equitable environments

Having opportunities for constructive social engagement and to develop a sense of connectedness

Learning social and emotional competencies (Sege & Brown, 2017).